Illuminating History

Named after a longtime donor, the Charles Young Museum and Exhibition Center will reveal the haunting history of an Italian town, a history uncovered by Professor David Soren’s 30 years of excavations in the region.

Photo of Terni Provence

The University of Arizona is partnering with an Italian town to create a museum and exhibition center showcasing the area’s storied history – a history that includes a devastating disease outbreak, witchcraft, and magic.

UA architecture students are creating exhibitions that tell the story of Lugnano in Teverina, a commune in the province of Terni in the central Umbria region of Italy that was hit hard by malaria in the middle of the fifth century. The student are part of the Arizona in Orvieto (Italy) Study Abroad Program.

Their work will be displayed in two churches in the community, which were built in 1587 and currently are being used for storage, pending their renovation.

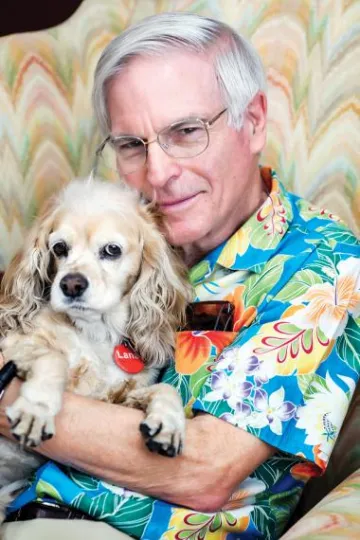

The museum project was conceived by David Soren, a UA Regents’ Professor of anthropology and classics, who also founded the Orvieto Study Abroad Program in 2001. Since 1986, Soren has worked on archaeological excavations in the Lugnano area, where his efforts have earned him honorary Italian citizenship.

Working closely with the local government in Lugnano, Soren is co-leading the project with Darci Hazelbaker, a lecturer in the UA College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture. This project is a prime example of the kind of interdisciplinary collaborations that Soren cultivates; he is often actively looking for ways to have his work “spin into” other departments.

Soren proposed the museum project to Lugnano mayor Gianluca Filiberti as a way to celebrate the town’s history and educate locals and tourists.

“I love the town, I love the people, and I love the mayor and his wife,” Soren said. “When I approached them with this idea, they said, ‘Let’s go for it. Let’s do everything we can do to create something for our town.’”

Help from a Longtime Supporter

The UA received $50,000 to restore the church roof from the Tucson-based Joseph and Mary Cacioppo Foundation. Currently led my Michael-Ann Young, the Cacioppo Foundation has also funded student travel and research for decades.

“Michael-Ann, her father, and her grandfather have been supporting my work for 32 years,” Soren said.

In recognition of the Cacioppo Foundation’s loyal support, the museum will be named the Charles Young Museum and Exhibition Center, in honor of Michael-Ann’s father.

David Pickel received funds from the Cacioppo Foundation when he was working on his master’s degree at the UA. He is now a Ph.D. student at Stanford and the director of excavations for the archaeological dig near Lugnano.

“I was fortunate enough to be awarded a Cacioppo Foundation Travel Award for the summer of 2014,” Pickel said. “This award allowed me to travel to Naples, Italy, for the first time, where I participated in a ceramics lab for an archaeological project excavating just below Mt. Vesuvius. I learned so much about Roman ceramics and what they can tell us about the ancient Romans.”

Soren’s work is also receiving support from an Italian consortium of towns – or communi – that includes Lugnano, in part by a grant of 170,000 euros (about $187,000 dollars).

Malaria and Magic

Part of what archaeology students will be tasked with communicating in the museum is the haunting history of Lugnano.

Soren’s many years of excavations there – with collaborators from Yale, Stanford, and elsewhere – uncovered a number of intriguing, often grim, finds. Their discoveries over time led to the revelation that Lugnano, about an hour north of Rome, was the site of a deadly malaria outbreak in the mid-fifth century.

While excavating the ruins of a sprawling and elegant villa – built around 15 B.C. and the size of a modern shopping mall – Soren and his colleagues made a gruesome discovery. The building, which had been rendered useless by foundational cracks by the mid-third century, had come to serve a new purpose by the middle of the fifth century: as a cemetery for infants and unborn fetuses.

The escalating pattern of infant burials at the site indicated an epidemic had hit the area and rapidly increased in deadliness over a short period of time, with the deceased buried together in an isolated area, probably because of fears of contamination.

Bone analysis would show that those buried there had likely fallen victim to Plasmodium falciparum malaria, or “blackwater fever,” a mosquito-borne illness that is particularly deadly to infants and unborn children. The disease may have found its way to the region through trade with Africa.

“Their children are dying, people are dying, aborted fetuses – it’s a horror story. And the community is responding in the only way it knows how: with magic and ritual. All of that is quite a story that this exhibit can tell.”

—David Soren

The archaeological evidence suggests residents of Lugnano, desperate to control the outbreak, turned to traditional black magic and sorcery for help. Soren and his colleagues found the remains of 13 puppies, which appeared to have been sacrificed in line with the belief that puppies can ward off evil. They also found two copper cauldrons filled with ash from possible offerings, as well as burials that included a toad and raven’s claw – common weapons of witchcraft against disease and evil.

The oldest child found at the site, estimated to be 2 to 3 years old, had stones and a large tile weighing down her hands and feet, probably placed there to keep her from rising from the dead. Archaeologists also found an abundance of honeysuckle, which was once used to treat fever and enlarged spleen – a condition that can be caused by malaria.

“The thing I found really interesting is the response of the community to crisis,” said Soren. “Their children are dying, people are dying, aborted fetuses – it’s a horror story. And the community is responding in the only way it knows how: with magic and ritual. All of that is quite a story that this exhibit can tell.”

Soren is excited about new developments with the site due to satellite imagery. “We now know that the villa we are excavating is 100 times bigger than we thought.”

For Soren, whose time in Lugnano has endeared him to the community, the project is personal.

“I really like setting things in motion where the result is something positive and lasting,” he said. “That gives me a great deal of personal satisfaction, and especially helping communities. The feeling you get from doing something like that is something money can’t buy.”

This story originally appeared in the SBS Developments 2018 magazine