UArizona Linguist Selected as AAAS Fellow

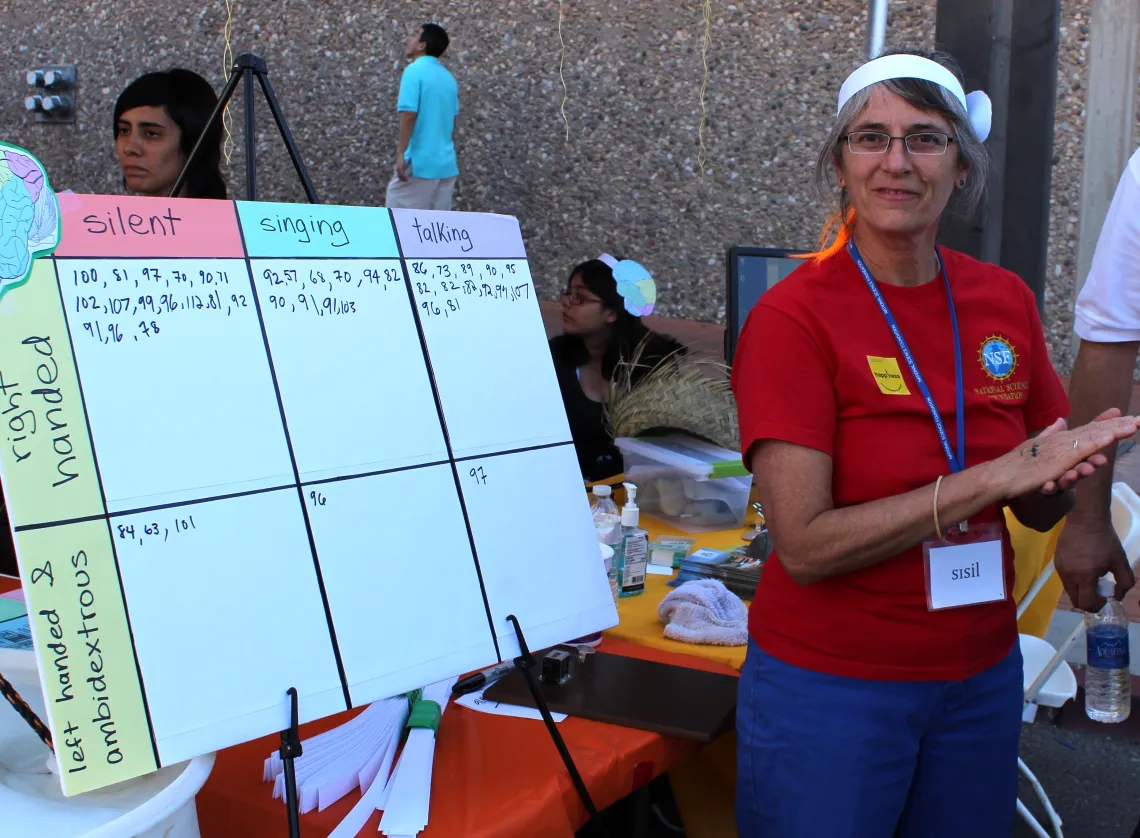

Cecile McKee at the Tucson Festival of Books

University of Arizona linguist Cecile McKee has been elected a 2021 Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, or AAAS, the world’s largest general scientific society.

McKee is being recognized for “distinguished contributions to developmental psycholinguistics, particularly experimental design for demonstrating children’s knowledge of syntax, and for distinguished service in promoting public awareness of the significance of linguistic study.”

The 2021 class of AAAS Fellows includes 564 scientists, engineers, and innovators spanning 24 scientific disciplines who are being recognized for their scientifically and socially distinguished achievements. The 2021 cohort also includes A. Elizabeth “Betsy” Arnold, professor of plant sciences, and Carol Gregorio, head of the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, from the University of Arizona.

The tradition of electing AAAS Fellows began in 1874. AAAS Fellows are elected each year by their peers serving on the Council of AAAS, the organization's member-run governing body. The title recognizes important contributions to scientific disciplines, including pioneering research, teaching and mentoring, and advancing public understanding of science.

McKee is a professor in the Department of Linguistics in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. She is also the director of the Developmental Psycholinguistics Laboratory and affiliated with the Department of Psychology, the the Cognitive Science Program, and the Second Language Acquisition and Teaching Program.

During her career, McKee has also been the director of the Linguistics Program for the National Science Foundation, director of the SBS Research Institute, associate dean of research for the College of SBS, and director of Research Development Services for UArizona’s Research, Innovation and Impact. Most recently, she chaired the AAAS’s section Z – language and linguistics.

“This is a big honor because the citation mentioned things that I have cared about my whole career,” McKee said. “And because I'm in a category [linguistics] that doesn't usually get this award, this is a great opportunity to talk about what science is. In particular, the AAAS recognizes science as a collection of processes rather than defining science by the object of investigation, such as planets or fish.”

“I am delighted that Cecile has been recognized, not only for her important research on children’s language development but also for her unflagging commitment to public engagement and science education,” said John Paul Jones III, dean of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Demonstrating Children’s Knowledge of Syntax

McKee studies young children’s language development, recently focusing on how fast and how fluently they talk.

How much of language acquisition is influenced by innate factors and how much is influenced by external factors is a continuing debate. University of Arizona Professor Noam Chomsky is the linguist who proposed Universal Grammar, a theory that certain critical elements of grammar are innate and so guide children’s mastery of all languages. McKee recalls being introduced to the seminal work of Chomsky early in her career.

“When I was a baby linguist at the University of Connecticut long ago, I used to drive up to MIT to listen to the part of Noam Chomsky’s classes that were open to anyone,” McKee said. “The ideas that he has proposed very much affected my research and so now it so amazing to be where he is.”

McKee has developed innovative ways to examine complex syntax in young children.

Cecile McKee with University of Arizona students at Children’s Museum Tucson.

“For much of my research, I wanted to look at whether children knew something about their language that was either very rare or very complex. And so I spent a lot of time developing new ways to put two-year-olds in experiments probing their grammatical knowledge. And the reason that matters is that various contrasting theories care very much about that early end. Once a kid is about three or four years old, syntactically, they're pretty much done. We find they perform like adults in certain experiments.”

McKee explains that many researchers, such as developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, emphasized naturalistic ways of observing children. The problem with this, McKee said, is that if a child doesn’t do some particular linguistic thing, you might conclude that that they don’t know how.

“Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. So just because a kid doesn't do something, doesn't mean he can't do it,” McKee said. “I would argue you might have missed it because it's rare or you didn't ask for it in a way the child understood. So you need a more sophisticated examination of what the child knows.”

McKee devised games where if the child plays enthusiastically, they say or understand syntactic constructions that they can't possibly have heard before.

Piagetian theories predict slow and error-prone progress towards the adult system, with faster learning on the more commonly occurring elements of language, McKee said. The theory of Universal Grammar generally predicts early and easy mastery of syntax. McKee’s experiments support the latter theory because they reveal sophisticated syntax in very young children, even of rarely occurring elements of language.

Engaging with the Public

McKee’s experience at NSF prompted her to prioritize engaging with the public. She became convinced that scholars should not only do state-of-the-art research but should also be sharing their research with broader audiences, including people who aren't at universities.

“I drank the Kool-Aid,” McKee said. “If you are using public money to do your science, you need to figure out a way to get it across to people other than the people who read the journals you publish in.”

The University of Arizona team, including Cecile McKee and students, NSF sent to the 2014 USA Science and Engineering Festival.

For many years now, McKee – often accompanied by a team of students – has been active in public engagement at K-12 schools, science and cultural festivals, including Science City at the Tucson Festival of Books and Tucson Meet Yourself. Her team presented at NSF’s pavilion at the 2014 USA Science and Engineering Festival in Washington DC. She has participated in AAAS’s Family Science Days every year since 2015. She also collaborated with the Children's Museum Tucson, as part of a UArizona class providing special engagement opportunities for undergraduate students.

During public engagement activities, the team presents a range of hands-on science activities designed for people of all ages. Activities have included audio and video recordings of greetings in various languages and samples of the approximately 800 sounds found in the 7,000 languages spoken around the world. Team members also lead visitors through a finger-tapping exercise to demonstrate how the left hemisphere of the brain handles language.

McKee likes to explore general linguistics questions, such as how languages differ, why it can be hard to learn languages, and why people have different accents.

“I am amazed by the kinds of conversations that you can have engaging with the public,” McKee said. “You often find out that people have right or wrong ideas about language. Both are fascinating.”

McKee says at science fairs, there’s often a focus on “rocks and rockets,” and she enjoys explaining how language can be studied scientifically and encouraging science interest in a variety of people by showing them that you can aim science practices at “anything that floats your boat.”