The Work of the Historian

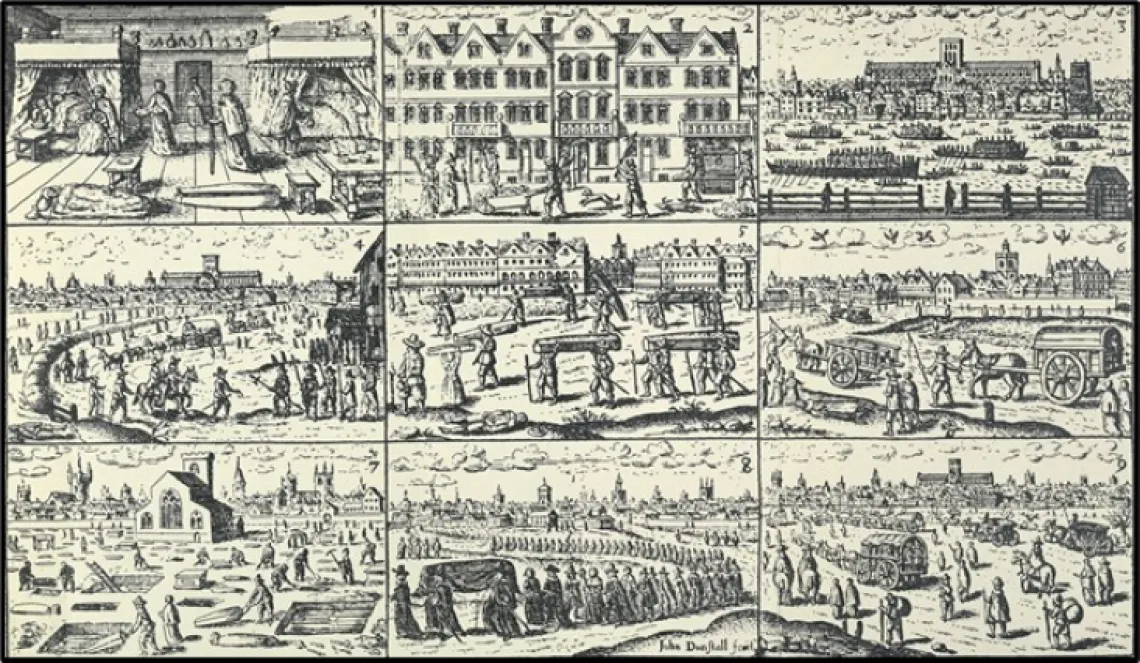

Source: John Dunstall, London Scenes of the Plague 1665-1666 (detail). Museum of London. ID no. 42.39/142

In recent months, as I was delving into my sabbatical research, I have been thinking not only of my own projects but also more generally about the work of a historian and what it means to research the past. Every historian has a different story about how they became interested in history, but I think what motivates us all is the quest to comprehend the motivations and actions of people in the past. We want to understand the dynamics of human behavior and human interaction—with other humans, animals, and the environment—and how individual and collective decisions shaped the course of history in the short and long term.

Ute Lotz-Heumann

Historians are mostly practitioners, and they tend to focus their attention on case studies firmly rooted in time and place. But there are more philosophical questions that lurk just beneath the surface of what we do. Many of these questions are concerned with whether it is necessary for historians to have experienced what they write about. Do you need to be a citizen or resident of a modern nation state to research the geographical region that this nation state occupies today? Does experiencing a pandemic make historians better at understanding epidemics in the past?

I would mostly argue no because early twenty-first century experiences are shaped by their specific political, social, cultural, and scientific contexts in a way that makes them fundamentally different from the experiences of the early modern Europeans that we research in the Division for Late Medieval and Reformation Studies.

Having said that, it often strikes me in my research that certain aspects of human life—the quest for self-preservation, altruism, and struggling with moral dilemmas (even if the underlying morals may be very different from today), for example—seem to be universal.

My sabbatical projects—print and propaganda in early modern Ireland, the perception of healing waters in early modern Germany, and the diary of Samuel Pepys—have all given me a lot of food for thought in this regard. Let me give you three brief examples from Samuel Pepys’s diary. During the summer months of 1665, when the plague ravaged London, Pepys recorded multiple moral dilemmas in his diary.

In one instance in mid-July, Pepys was “much troubled” by the news that “officers do bury the dead in the open Tuttle fields,” while churchyard burials were only available to the wealthy. Later, when the servant of Captain Cocke, one of Pepys's colleagues in the Navy Office, had fallen ill and died, Pepys and his colleagues asked Cocke to no longer come to the office—until “the Searchers,” usually older women hired to go into houses and determine the cause of death, found that “the fellow did not die of the plague.”

And in early September, Pepys recorded the heart-breaking story of the only surviving child of a saddler and his wife who had lost all their other children to the plague. The naked child (for fear of clothes carrying the disease) was lowered out of a window of their shut-up house and then taken to Greenwich. A complaint had been made against the man who had transported the child, but Pepys agreed that the child should be allowed to remain in Greenwich.

I think these episodes all speak to the perception of personal and societal risk, fairness, and empathy in a situation of threat and uncertainty. While the circumstances were very different, we can—and should—relate to and reflect on the moral dilemmas so vividly represented by Pepys.

##

“The Work of the Historian” was published in the Spring/Summer edition of the “Desert Harvest,” published by the Division for Late Medieval and Reformation Studies. Ute Lotz-Heumann is the Heiko A. Oberman Chair in Late Medieval and Reformation History and the director of the Division for Late Medieval and Reformation Studies in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences.