Biodiversity in a Bottle: Uncovering Mexico’s Traditional Fermented Beverages

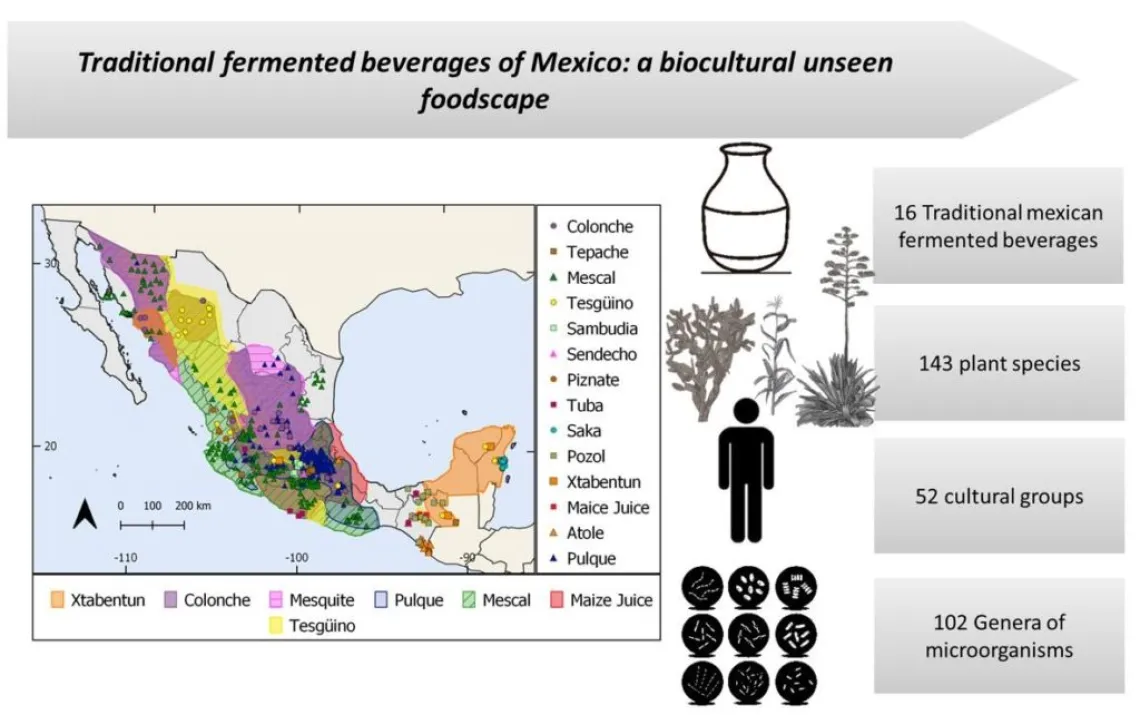

For thousands of years, Mexico’s home brewers, cooks, foragers and farmers have elaborated 16 distinctive sets of fermented and probiotic beverages from over 140 plants species and thousands of strains or yeasts and bacteria.

Now – using microbiological, ethnobotanical and genetic advances – an interdisciplinary team from five universities, including the University of Arizona, have systematized information on the diversity and cultural history of traditional Mexican fermented beverages, documented their spatial distribution, and identified the main research trends and topics needed for their conservation and recovery.

The team, based at the Institute for Ecosystem and Sustainability Research at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, has daylighted unseen dimensions of foodscapes in both Mesoamerica and Aridamerica.

The results were published in the article “Traditional Fermented Beverages of Mexico: A Biocultural Unseen Foodscape” in the international journal Foods as part of the special issue “New Insights into Food Fermentation.”

A team led by ethnoecologist Alejandro Casas and including University of Arizona Southwest Center research scientist Gary Paul Nabhan documented probiotic beverages elaborated in Northwest Mexico and Arizona.

Gary Paul Nabhan

Their findings suggest that cacti, agaves and cereal grains comprised the primary substrates of these traditional ferments, but in each region and locality, a distinctive set of plant roots, leaves, fruits and stems were added as fermentation catalysts, flavorants, colorants and stabilizers.

A large number of bacterial strains and yeasts – in addition to common brewer’s yeasts and water kefir grains – enabled the nutritional transformation of these raw materials into a wide array of unique nutritionally rich, probiotic beverages.

By mapping regional variations and using ecological niche theory to explain the radiation of plant carbohydrates into so many differentiated beverages, the research team provides the first comprehensive analysis of Mexico’s traditional “ferments.”

In Northwest Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, ethnobotanist Nabhan and microbiologist Patricia Lappe-Oliveras identified the indigenous use of four genera of cacti, in addition to a dozen agaves, three sotol species and many varieties of maize in the fermentation of festive and ceremonial beverages.

“The naturally-occurring yeasts and kefir-like tibico grains found in association with prickly pear cacti, saguaro fruit, century plants and desert spoons (sotols) likely tolerate much higher ambient temperatures than those from the semi-arid highlands and wet tropical forests,” Nabhan explained.

Lead author César Ojeda-Linares and the research team also determined that traditional Mexican fermented beverages (TMFBs) are dynamic across time and space, forming heterogenous foodscapes that are valuable biocultural reservoirs essential to the nutritional health of humans in a changing climate.

The team cautions that with the globalization of our food systems and aggressive marketing by the producers of soft drinks, beers, and wine, many of these traditional and more healthful beverages have fallen out of fashion and face local or broad extinction.

Nabhan analyzed 70 recipes for traditional fermented beverages in Mexico reported by Don Antonio Pineda in 1791 to see which still occur in some form today. Using a version of Pineda’s report translated and published by the University of Arizona’s Journal of Arizona and the West in 1963, Nabhan was able to find areas where some of the more forgotten ferments may still be elaborated for home use, but not commercialized. He discovered that some of the rare agave varieties used in those historic ferments may still occur in several states, but were employed for other uses once Mexico’s Ley Seca established Prohibition-like bans on commercial alcohol production over a century ago.

“Now that the days of Prohibition are over and there is a great need for arid-adapted crops with highly-efficient water use, some of these traditional agave and cactus varieties should be revived for the local production of healthful beverages,” Nabhan suggests. “In fact, traditional beverages such as tepache, tesguino and colonche have made a comeback in the Tucson, Arizona region since it received recognition as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy. These traditional beverages are also being employed by mixologists in novel cocktails now being featured in nearly every state of Mexico.”

The authors say there is more to learn about the composition and societal value of Mexico’s traditional fermented beverages.

“Many of Mexico’s finest microbiologists and ethnobotanists are giving ever-greater attention to this fascinating but once-forgotten foodscape, but even they are willing to admit that we’re just beginning to scratch below the surface of understanding all the biodiversity in these bottles of blessed ferment,” Nahban said.