Annual Poverty Project Focuses On Neighborhood Satisfaction, Health

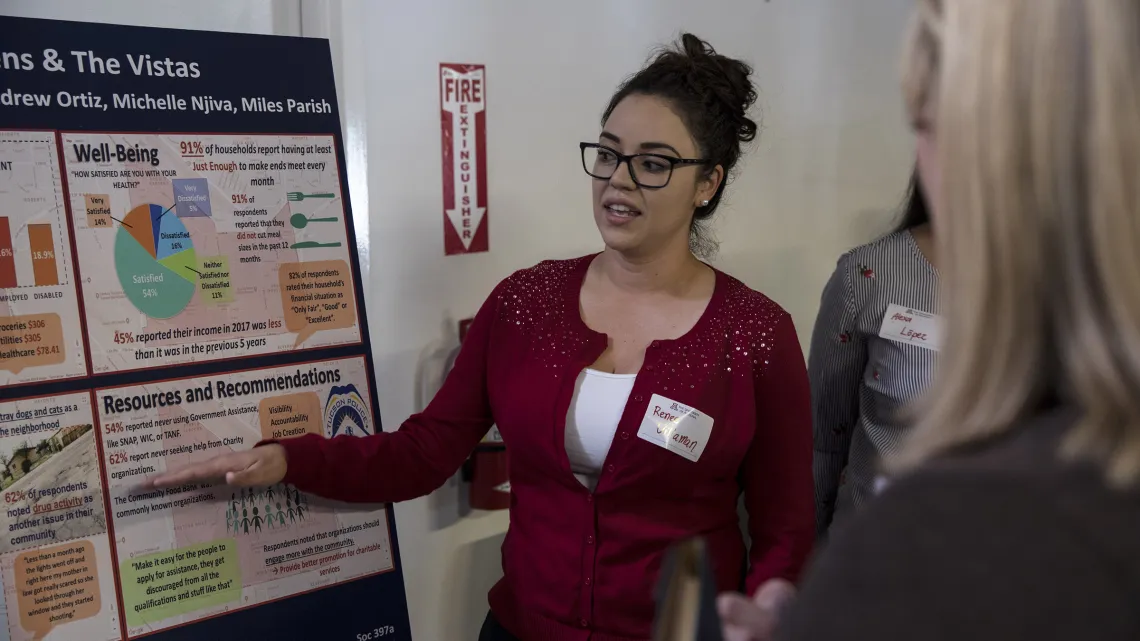

UA Student Reneé Villaman explains findings from the Poverty in Tucson Field Workshop to community members.

Low-income households in Tucson are less satisfied renting and living in north and east Tucson neighborhoods, according to findings presented by University of Arizona students from the Poverty in Tucson Field Workshop. In addition, an analysis of data over four years reveals that low-income households are using less government assistance and more charitable services.

During the fourth annual community forum, held May 10, 2018, at Habitat for Humanity Tucson, students presented data from the Tucson Wellbeing Survey to more than 200 community members, city officials and nonprofit organizers, the largest audience to date.

The event was the culmination of the students' semester-long efforts to collect data from low-income households. This year, the survey introduced questions on neighborhood life and satisfaction, as well as health and quality of life.

The Poverty in Tucson Field Workshop was developed to help local governments and nonprofit organizations better understand the causes and consequences of poverty, which impacts 25 percent of all households and more than 33 percent of all children in Tucson. The workshop has been an ongoing research collaboration between the School of Sociology, the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, and local nonprofits, including Habitat for Humanity Tucson, the Community Foundation of Southern Arizona and the Community Food Bank for Southern Arizona.

This year’s class interviewed 250 households from eight high-poverty census tracts in Tucson. Of the respondents, 14.8 percent were unemployed; the rest were retired or working full or part time.

Health and quality of life

Using questions from the World Health Organization, the students asked respondents about their health. Twenty-eight percent of those living at the poverty level rated their current health poor or fair. This was higher than the 16 percent of those living in extreme poverty who rated their health poor or fair, probably due to the increased governmental health benefits available to this lower income group. The national average for those who rate themselves in poor or fair health is 10 percent, so poverty remains correlated with poorer health outcomes.

Neighborhood life and satisfaction

This year, the Poverty Project deepened its partnership with Habitat for Humanity Tucson, according to Brian Mayer, associate professor in the UA School of Sociology and director of the project. The survey included questions to assist with Habitat’s neighborhood partnership program, such as whether the respondents consider their neighborhood a good place to raise kids.

“We use the data to help us know how to approach the community members in the neighborhoods,” said T. VanHook, chief executive officer with Habitat for Humanity Tucson.

Fifty-three percent of respondents were satisfied with where they lived, but there were geographic differences. Rated highest were central Tucson (63.6 percent) and South Tucson (61.3 percent) with the east side close to the Air Force base (44.1 percent) and the north side near the Amphi neighborhood (35.2 percent) rating lower.

Sixty-three percent of households complained about stray cats and dogs in their neighborhood, poor street conditions, speeding vehicles, drug use and litter.

Mayer, who is also a fellow in the Agnese Nelms Haury Program in Environment and Social Justice, points out that many support services are located in downtown and South Tucson areas. “There are far fewer charities that are located further north, so people may feel isolated and disconnected from help.”

Another possible explanation for the neighborhood variation ties to an additional survey result: Those who rent, compared to those who own their home, are 1.6 times more likely to be dissatisfied with their neighborhood.

“In the north, home ownership rates are low, only 30 to 40 percent,” said Mayer. “Amphi High School teachers told us they have a 46 percent turnover rate in students from year to year. This has much to do with the rent and people leaving to find affordable housing.”

The transitive nature of a high concentration of renters can also undermine community cohesiveness and satisfaction. Conversely, the research team has found a tighter community network in South Tucson.

“Last year we looked at collective efficacy,” Mayer said. “People in South Tucson, especially in more Hispanic-dominated areas, felt like they could call on each other to a much higher degree.”

Student Nuve Brambila, who conducted surveys on the South-side, noticed – and was impressed – by this when she conducted her interviews.

When asked the question “What do you do when you are struggling for money?” 42.9 percent of respondents said work overtime, and 28.6 percent said ask for help from family.

“There is this idea that people living under the poverty level are lazy and just using government resources. But I found that these people were very hard working,” Brambila said. “They were really connected and tried to seek help from each other when trying to overcome poverty.”

Housing, food and the service gap

As in previous years, housing overburden (spending more than 30 percent of income on housing) remained a problem, with 92.5 percent of those at the poverty level being overburdened, which translates into less money for food, healthcare and educational expenses.

In addition, eighteen percent of respondents cut meals due to a lack of money. The data also revealed that without SNAP benefits, there would be a 40 percent increase in food insecurity.

The number of homes not accessing government and charitable assistance also remained high, with 46.2 percent of those in extreme poverty reporting that they never use government assistance. In addition, 48.7 percent of this group report never receiving help from a charity or nonprofit.

“I spoke with some people who have negative views about receiving government assistance,” said Hannah Hertenstein, who is majoring in sociology and in family studies and human development.

Haley Urban, who is majoring in sociology and in care, health, and society, said that several respondents also mentioned ways that programs were challenging to access, such as being open only during their work hours or being hard to get to on the bus.

Mayer analyzed this “service gap” for the four years the class has been collecting data. The number of people receiving government assistance has decreased by nearly 20 percent; however, the number of people accessing charitable services has increased by 15 percent. “As the state retracts from the social safety net, it looks like charities are reaching more people,” Mayer said.

100% student engagement

The workshop demonstrate the UA's commitment to 100% Engagement. Students in the course gain hands-on social research experience, an enhanced understanding of poverty-related issues, and real-world professional skills.

“I couldn’t ask for a better experience, because it was so valuable to my education and with what I want to do with my career,” said Hertenstein, who wants to do community work.

Students also mentioned how the experience taught them time management and how to communicate better with strangers.

Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild said he appreciates that the class not only produces useful information, but also cultivates compassion and a determination to act.

“Knowledge without action is really a waste,” Rothschild said.

Mayer says that next year, they’re adding a new course as a follow-up to the poverty workshop called Building Healthy Communities, where the students will work directly with the Tucson Fire Department's TC-3 program, a collaborative community care program designed to assist the most vulnerable members of the Tucson community by connecting them to appropriate community resources.

Brian Thompson, captain and TC-3 manager with the Tucson Fire Department, attended the poverty forum with several other firefighters. “It is really exciting what these students are doing,” Thompson said. “We work closely with Dr. Brian Mayer, and he’s been a huge advocate for the TC-3 program.”

Mayer added, “Through this collaboration, students will be challenged to develop innovative solutions to help people that regularly call 9-1-1 for nonemergency reasons find the types of help that they need.”